Namibia (/nəˈmɪbiə/ ⓘ, /næˈ-/), officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country in Southern Africa. Its western border is the Atlantic Ocean. It shares land borders with Zambia and Angola to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and east. Although it does not border Zimbabwe, less than 200 meters (660 feet) of the Botswanan right bank of the Zambezi River separates the two countries. Its capital and largest city is Windhoek.

he Ovambo people (pronounced [ovambo]), also called Aawambo, Ambo, Aawambo (Ndonga, Nghandjera, Kwambi, Kwaluudhi, Kolonghadhi, Mbalantu), or Ovawambo (Kwanyama), are a Bantu ethnic group native to Southern Africa, primarily modern Namibia. They are the single largest ethnic group in Namibia, accounting for about half of the population.Despite concerted efforts from Christian missionaries to wipe out what were believed to be ‘pagan practices’, they have retained many aspects of their cultural practices. They are also found in the southern Angolan province of Cunene, where they are more commonly referred to as “Ambo”. The Ovambo consist of a number of kindred Bantu ethnic tribes who inhabit what was formerly called Ovamboland. In Angola, they are a minority, accounting for about two percent of the total Angolan population.

There are about 2 million people of the Ovambo ethnic group, and they are predominantly Lutheran (97%) and traditional faith (3%)

The Skeleton Coast is the northernmost part of the Atlantic coast of Namibia, and known as one of the wildest and most hostile coastal stretches in the country. It is a sandy and desolate area, almost 6500 square miles of stunning Skeleton Coast National Park. The waters off this place are famous for their strong currents, dense fogs and treacherous sand banks in constant motion. These extreme climatic conditions, when combined with strong sand storms has been considered the cause of the sinking of over a thousand ships. Many shipwrecks, together with the skeletons of large cetaceans, are still scattered on the beach as far as the hinterland.

The driest country in sub-Saharan Africa, Namibia has been inhabited since pre-historic times by the San, Damara and Nama people. Around the 14th century, immigrating Bantu peoples arrived as part of the Bantu expansion. Since then, the Bantu groups, the largest being the Ovambo, have dominated the population of the country; since the late 19th century, they have constituted a majority. With a population of 2.55 million people today, Namibia is one of the most sparsely populated countries in the world.

This desolate coastal strip with a threatening denomination and has often been characterized by massive storms, due to the cold Atlantic currents meeting with the warm currents of the African continent. Experienced Portuguese navigators called it the “beach of hell”, while the Bushmen gave it the name of “land that God created in anger.” The only way not to get trapped in this portion of the coast was to navigate completely around it.

The Skeleton Coast, despite its particularly prevalent inhospitality, still carries charm. The humidity provided by the fog that pushes inwards for miles guarantees the life of many animal species – from insects to reptiles, and large mammals such as elephants, giraffes and lions. The shipwrecks on the beach and at sea, attract only the most adventurous travelers, mostly photographers looking for spectacular and surreal landscapes. An infinite space made of sand, water and nothing else, where nature once again demonstrates its inimitable power.

In 1884, the German Empire established rule over most of the territory, forming a colony known as German South West Africa. Between 1904 and 1908, it perpetrated a genocide against the Herero and Nama people. German rule ended during the First World War with a 1915 defeat by South African forces. In 1920, after the end of the war, the League of Nations mandated administration of the colony to South Africa. From 1948, with the National Party elected to power, this included South Africa applying apartheid to what was then known as South West Africa. In the later 20th century, uprisings and demands for political representation by native African political activists seeking independence resulted in the United Nations assuming direct responsibility over the territory in 1966, but the country of South Africa maintained de facto rule. In 1973, the UN recognized the South West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO) as the official representative of the Namibian people. Namibia gained independence from South Africa on 21 March 1990, following the Namibian War of Independence. However, Walvis Bay and the Penguin Islands remained under South African control until 1994.

Namibia is a stable multi-party parliamentary democracy. Agriculture, tourism and the mining industry – including mining for gem diamonds, uranium, gold, silver and base metals – form the basis of its economy, while the manufacturing sector is comparatively small. Namibia is a member state of the United Nations, the Southern African Development Community, the African Union and the Commonwealth of Nations.

The name of the country is derived from the Namib desert, the oldest desert in the world. The word Namib itself is of Nama origin and means “vast place”. The name was chosen by Mburumba Kerina, who originally proposed “Republic of Namib”. Before Namibia became independent in 1990, its territory was known first as German South-West Africa (Deutsch-Südwestafrika), and then as South West Africa, reflecting its colonial occupation by Germans and South Africans, respectively.

The dry lands of Namibia have been inhabited since prehistoric times by the San, Damara, and Nama. For thousands of years, the Khoisan peoples of Southern Africa maintained a nomadic life, the Khoikhoi as pastoralists and the San people as hunter-gatherers. Around the 14th century, immigrating Bantu people began to arrive during the Bantu expansion from central Africa.

The Namib, considered to be the oldest and driest desert in the world, is certainly also one of the most astonishing, with its monumental dunes, petrified acacia forests, an extraordinary microclimate that allows the survival of endemic flora and fauna, and scenic ghost towns, engulfed in diamond sands tinged with red, pink, orange and ochre. A unique desert of rock and sand that flows directly into another desert made of water, the Atlantic Ocean, populated by whales and sea lions. The Namib, with its naturalistic surprises and colour ranges, will enchant and amaze even the most experienced traveller.

The first images that come to mind when one thinks of the Namib are the incredible desert landscapes of Sossusvlei, nestled between the world’s highest and most colourful dunes. We are in the heart of the Namib-Naukluft National Park, an immense eco-region that stretches parallel to the Atlantic coast, between the colonial towns of Luderitz in the south and Swakopmud and Walvis Bay in the north, extending its course through the Namib’s stony interior glades and the rocky canyons of the Moon Valley, ascending northwards towards the borders of Damaraland, and plunging westwards directly into the ocean, past the high dune belts of spectacular Sandwich Harbour, to the Skeleton Coast with its impressive early 20th century shipwrecks.

True monuments of nature, each dune on Sossusvlei is given a name. Dune 45, the most scenic to climb, Big Daddy and Dune 7, the highest in the world (over 300 metres), and Dead Vlei, the famous dried-up salt flat, with its light soil tones contrasting with the grey of the petrified acacia trunks, and with the surrounding dunes that change colour continuously depending on the time of day. Surreal shades of white, ochre, pink, red, orange and the blue of the sky, for one of the most photographed spectacles of nature in the world.

With less than 20 millimetres of annual rainfall, dog days and glacial nights, the Namib Desert has a special microclimate that allows the miraculous survival of numerous endemic species of flora and fauna, thanks to the thermal moisture that forms in the collision with the cold ocean current of the Benguela, and that envelops everything in fog and condensation up to 60 km inland. Chameleons, beetles, vipers and lizards, as well as ostriches, hyenas and jackals, feed and hydrate on termites and condensation from the fog, which also allows sporadic vegetation to grow on the edge of the dune belts, feeding the oryxes, Namibia’s iconic animals, which have developed the ability to raise their body temperature above 40 °C during the hottest hours to prevent water loss. An extraordinary ecosystem that is reflected in the beauty of the surrounding landscape, desolate and magical at the same time.

It is precisely the phenomenon of the mists that has caused the highest number of shipwrecks in the world, populating the Namib’s coastline, the so-called Skeleton Coast, with human skeletons of sailors and the skeletons of ships that ran aground in the past centuries among the shoals emerging from the water and that today, with the advancing sands, are partly completely beached. A fascinating spectacle, which is now an integral part of the coastal landscape, home to some of the most populous colonies of sea lions in the world, as well as whales, sharks, dolphins, pelicans and pink flamingos. A coastline populated by aquatic fauna, and inhabited by man only in sporadic settlements founded in colonial times. Small towns where the first German settlers settled, with the intention of developing the mining industry, iron and especially diamonds, and deep-sea fishing. Small branches of the Rhine in the middle of the coastal desert, the towns of Luderitz, Swakopmud and Walvis Bay.

From Luderitz, within easy reach are the early diamond settlements of Kolmanskop, Elisabeth Bay or Pomona, now abandoned and swallowed up by the Namib dunes, ghost dwellings that, like the shipwrecks, or the abandoned cars of Solitaire, are now part of this desert land that has inexorably engulfed them, forever.

From the late 18th century onward, Oorlam people from Cape Colony crossed the Orange River and moved into the area that today is southern Namibia. Their encounters with the nomadic Nama tribes were largely peaceful. They received the missionaries accompanying the Oorlam very well, granting them the right to use waterholes and grazing against an annual payment. On their way further north, however, the Oorlam encountered clans of the OvHerero at Windhoek, Gobabis, and Okahandja, who resisted their encroachment. The Nama-Herero War broke out in 1880, with hostilities ebbing only after the German Empire deployed troops to the contested places and cemented the status quo among the Nama, Oorlam, and Herero.

In 1878, the Cape of Good Hope, then a British colony, annexed the port of Walvis Bay and the offshore Penguin Islands; these became an integral part of the new Union of South Africa at its creation in 1910.

The first Europeans to disembark and explore the region were the Portuguese navigators Diogo Cão in 1485 and Bartolomeu Dias in 1486, but the Portuguese did not try to claim the area. Like most of the interior of Sub-Saharan Africa, Namibia was not extensively explored by Europeans until the 19th century. At that time traders and settlers came principally from Germany and Sweden. In 1870, Finnish missionaries came to the northern part of Namibia to spread the Lutheran religion among the Ovambo and Kavango people. In the late 19th century, Dorsland Trekkers crossed the area on their way from the Transvaal to Angola. Some of them settled in Namibia instead of continuing their journey.

Namibia became a German colony in 1884 under Otto von Bismarck to forestall perceived British encroachment and was known as German South West Africa (Deutsch-Südwestafrika). The Palgrave Commission by the British governor in Cape Town determined that only the natural deep-water harbour of Walvis Bay was worth occupying and thus annexed it to the Cape province of British South Africa.

In 1897, a rinderpest epidemic caused massive cattle die-offs of an estimated 95% of cattle in southern & central Namibia. In response the German colonizers set up a veterinary cordon fence known as the Red Line. In 1907 this fence then broadly defined the boundaries for the first Police Zone.

From 1904 to 1907, the Herero and the Namaqua took up arms against brutal German colonialism. In a calculated punitive action by the German occupiers, government officials ordered the extinction of the natives in the Ova Herero and Namaqua genocide. In what has been called the “first genocide of the 20th century”, the Germans systematically killed 10,000 Nama (half the population) and approximately 65,000 Herero (about 80% of the population). The survivors, when finally released from detention, were subjected to a policy of dispossession, deportation, forced labor, racial segregation, and discrimination in a system that in many ways foreshadowed the apartheid established by South Africa in 1948. Most Africans were confined to so-called native territories, which under South African rule after 1949 were turned into “homelands” (Bantustans). Some historians have speculated that the German genocide in Namibia was a model for the Nazis in the Holocaust. The memory of genocide remains relevant to ethnic identity in independent Namibia and to relations with Germany.

The German minister for development aid apologized for the Namibian genocide in 2004. However, the German government distanced itself from this apology. Only in 2021 did the German government acknowledge the genocide and agreed to pay €1.1 billion over 30 years in community aid.

Known as Africa’s apex predator, not many people know of or have seen the mysterious desert lions of Namibia. It’s astounding to even think that lions can survive in such a merciless environment.

Found mostly outside the protected areas in northern Namibia’s Kunene region, the desert lions are hardy and highly adapted to survive in these extreme conditions. They don’t need to drink water but get all the moisture they need from their kill such as ostrich, gemsbok and the occasional seal (if they dare catch one).

These magnificent creatures are unique to the Namib Desert and are vital in sustaining the Namibian tourism industry. Their biggest threat is man, in particular local communities that shoot them when they prey on their cattle. It’s thus crucial that conservation projects such as The Desert Lion Conservation Project are supported to manage not only the human-lion conflict, but also to monitor their behavior and population.

A fascinating new movie entitled ‘Vanishing Kings – Namibia’s Desert Adapted Lions’ is set to be released this year. It tracks a family of desert lions, their trials and tribulations and ultimate survival against all the odds through Namibia’s Kaokoveld. Your best chances of seeing these elusive and rarely seen lions is from Hoanib Skeleton Coast Camp.

Another one of Namibia’s incredible desert-adapted animals is the unique and rare desert-dwelling elephant. Found only here and in Mali, these gentle desert giants can be found mostly in the rocky mountains, sandy desert, and stony plains of the Kunene region.

They are fascinating creatures, and it’s hard to believe that an animal that usually needs plenty of water per day can survive in this harsh climate and go without water for up to three days. Desert elephants usually travel in family groups made up of a female and her young as well as sisters and aunties. The adult bull, on the other hand, is solitary and can traverse large areas.

They are fascinating creatures, and it’s hard to believe that an animal that usually needs plenty of water per day can survive in this harsh climate and go without water for up to three days. Desert elephants usually travel in family groups made up of a female and her young as well as sisters and aunties. The adult bull, on the other hand, is solitary and can traverse large areas.

These animals have adapted to desert life by having smaller bodies, broader feet and longer legs than their African relatives. In the wet season, they prefer fresh young leaves and buds, but can survive on a myriad of drought-resistant plants in the dry season.

If you want to see these incredible elephants first-hand, we suggest booking into the luxurious Mowani Mountain Camp situated amongst a cluster of massive boulders in Namibia’s Damaraland. Switch off all your devices and succumb to the peaceful beauty of this prehistoric land with its dramatic stark landscape.

Black Rhino If you want to see one of Africa’s rarest and sadly most endangered inhabitants in the wild, then going black rhino tracking in Namibia’s Damaraland is right at the top of your bucket list.

This part of Namibia is blessed with a wealth of desert-adapted plants, insects and animals. Slightly larger than their South African counterparts, the desert black rhino sport larger feet and have adapted to become great mountaineers, able to scale a mountain ledge to catch a cool breeze from the Atlantic, get out of the heat of the day and forage for tasty succulents.

They are also able to cover vast areas as large as 2500 km² in search of food. Usually rhinos need to drink plenty of water every night, but the desert rhinos have adapted in such a way that they only need to drink every third or fourth night, even though they have to cover huge distances.

If you seek wide open spaces and an encounter with the black rhino, we suggest either visiting Damaraland Camp set in the Torra Conservancy or Desert Rhino Camp in the rocky hills of the Palmwag Concession, both from the Wilderness Safari portfolio of camps and lodges. Known for awe-inspiring stargazing, as well as the location for the largest free-roaming black rhinos in Africa, this is a must-see destination full of desert plains and ancient rocky valleys.

During World War I, South African troops under General Louis Botha occupied the territory and deposed the German colonial administration. The end of the war and the Treaty of Versailles resulted in South West Africa remaining a possession of South Africa, at first as a League of Nations mandate, until 1990. The mandate system was formed as a compromise between those who advocated for an Allied annexation of former German and Ottoman territories and a proposition put forward by those who wished to grant them to an international trusteeship until they could govern themselves. It permitted the South African government to administer South West Africa until that territory’s inhabitants were prepared for political self-determination. South Africa interpreted the mandate as a veiled annexation and made no attempt to prepare South West Africa for future autonomy.

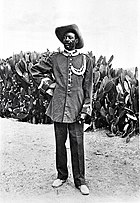

Hendrik Witbooi (left) and Samuel Maharero (right) were prominent leaders against German colonial rule. As a result of the Conference on International Organization in 1945, the League of Nations was formally superseded by the United Nations (UN) and former League mandates by a trusteeship system. Article 77 of the United Nations Charter stated that UN trusteeship “shall apply…to territories now held under mandate”; furthermore, it would “be a matter of subsequent agreement as to which territories in the foregoing territories will be brought under the trusteeship system and under what terms”. The UN requested all former League of Nations mandates be surrendered to its Trusteeship Council in anticipation of their independence. South Africa declined to do so and instead requested permission from the UN to formally annex South West Africa, for which it received considerable criticism. When the UN General Assembly rejected this proposal, South Africa dismissed its opinion and began solidifying control of the territory. The UN General Assembly and Security Council responded by referring the issue to the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which held a number of discussions on the legality of South African rule between 1949 and 1966.

South Africa began imposing apartheid, its codified system of racial segregation and discrimination, on South West Africa during the late 1940s. Black South West Africans were subject to pass laws, curfews, and a host of residential regulations that restricted their movement. Development was concentrated in the southern region of the territory adjacent to South Africa, known as the “Police Zone”, where most of the major settlements and commercial economic activity were located. Outside the Police Zone, indigenous peoples were restricted to theoretically self-governing tribal homelands.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, the accelerated decolonization of Africa and mounting pressure on the remaining colonial powers to grant their colonies self-determination resulted in the formation of nascent nationalist parties in South West Africa. Movements such as the South West African National Union (SWANU) and the South West African People’s Organization advocated for the formal termination of South Africa’s mandate and independence for the territory. In 1966, following the ICJ’s controversial ruling that it had no legal standing to consider the question of South African rule, SWAPO launched an armed insurgency that escalated into part of a wider regional conflict known as the South African Border War.

Another one of Namibia’s ingenious desert-adapted creatures is the fog beetle which relies on foggy conditions that prevail near the coast where the cold Atlantic Ocean meets the hot land, to collect drinking water. In the early mornings, this clever little beetle can be found doing a headstand whilst allowing the fog to condensate on its back and trickle down to its mouth. The fog beetle has been known to drink up to 40% of its body weight during its morning gymnastics.

Other fascinating desert-adapted wildlife of the Namib Desert include: Baboon, Leopard, Cheetah, Brown and Spotted Hyena, Klipspringer, Springbok, Steenbok, Cape and Bat Eared Fox, Hartmann’s Zebra, as well as many insects, reptiles, small mammals and even wild Desert Horses. These wild horses can be found in the region of the historical mining town of Luderitz. They are the feral descendants of German cavalry horses from WW1.

Whether you are seeking solitude in one of Africa’s most spectacular landscapes, or want to experience the highly developed techniques that these animals display in order to survive in the Namib environment, either way, book your desert adventure to this extraordinary country.